Physiology honours Dr. Patricia Brubaker, the “Godmother of GLP-2," who retires June 30th

Last Wednesday, June 22nd, Dr. Patricia Brubaker presented the final talk of her career to a packed audience of ardent fans. Everyone from former students to scientific colleagues, non-scientist friends, former department Chairs, and her beloved husband Steve piled into Room 2172 in the Medical Sciences building, and listened, rapt, as Dr. Brubaker shared the story of her life and career in a seminar entitled “Reflections on 45 years as a scientist.”

The talk took us from her childhood through her early discoveries about the glucagon-related peptides and culminated in a beautiful tribute to all of the students she’s mentored over the years who motivated her work. Make no mistake, Dr. Brubaker is a very serious scientist. She is also exacting, decisive, and direct – qualities all of her colleagues mentioned in their speeches after her talk. But what came up repeatedly, too, was Dr. Brubaker’s love of life; the value she places on having fun. In addition to the joy she finds in adventure trekking, which you can read more about in this excellent profile for the Banting and Best Diabetes Centre, we learned how much Dr. Brubaker values simply getting together with friends, colleagues, and students to enjoy good food and drink a glass of wine.

With that balance in mind, what follows are some highlights drawn from the wide-ranging chat we were lucky to have with her as she prepared for her seminar.

Trekkie childhood

Well, I’ve always been a little bit geeky, but honestly, watching Star Trek was the first life-altering moment that made me realize science was cool. I was nine years old at the time.

A few years after Star Trek first aired, Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, and throughout these years Reader’s Digest was putting out a series of articles called things like “I Am Joe’s Heart,” “I Am Jane’s Ovaries,” and so on – little profiles of the human body that I lived for. Those three things together put me on the scientific path.

I’m sure my parents thought I was this odd little child. My father was in the army, my mother was a teacher and librarian – they had no idea what science was! I don’t think they knew what to do with me! But they were so supportive. They said I could do whatever I wanted to do.

An early education

When I went into highschool in 1969, I focused on science, and continued to do so in CEGEP. It was there that I was mentored by Dr. Joe Schwarcz who totally turned me on to organic chemistry. He was the best teacher I’ve ever had in my life. He and his wife also welcomed students into their home, we skied together, all sorts of fun things. So not only did he open up the world of chemistry for me, he also taught us at an early age how to enjoy life. Which I’ve carried with me.

Toronto forever!

In university, I merged my interest in chemistry with my love of health science by specializing in biochemistry. I completed both my undergrad and PhD at McGill. Once I graduated, my husband, Steve, couldn’t get a job in Montreal, and I couldn’t get one in Ottawa where he was. So we decided we’d move to Toronto where we could both get jobs – we became part of the “Quebec diaspora.” In 1982, I started a postdocoral fellowship with Dr. Mladen Vranic in the Department of Physiology to work on intestinal peptides. After three years, Mladen and the Chair at the time, Dr. Harold Atwood, brought me on as faculty, and I landed a tenure-track position in 1992. And that was it! I never left.

Sure, there were lots of opportunities to leave Toronto. But I loved it here for a couple of reasons. First, I liked the Department. Second, I have a long-standing collaboration with Dr. Daniel Drucker. We’ve published forty-nine papers together. Losing that close connection with Dan, especially before the internet, was a big consideration. And finally, my husband is self-employed, and would have lost his business had we moved. Often people have said, “Why don’t you apply here? Why don’t you go there?” But I’ve stayed and I’ve been very happy in Toronto.

GLP-1: the science behind Ozempic

In my career, I’ve mainly studied two glucagon-related peptides – GLP-1 and GLP-2. The first has gone on to become Ozempic and related drugs. Daniel Drucker and I were not the only people in the world studying this by any means, but my lab did contribute early studies on how GLP-1 suppresses appetite. Our studies, collectively with those of other scientists, helped to solidify this notion that long acting GLP-1 receptor agonists are good for blood glucose levels and help you lose weight. And this understanding eventually led to the drugs we have today.

Certainly for people with type two diabetes, those drugs are huge news. And for people who need to lose weight and are unable to do so through diet and exercise alone – and there’s lots of reasons why, it’s not just willpower! – the only choice used to be surgery. That’s pretty dramatic, right? So these drugs are really life-changing.

I admit I’m frustrated to see all these people using the drug to fit into their Oscars gowns and whatnot. I mean, maybe it’s unfair to blame them, but it’s really an abuse of the drug. And to hear people complain about the side effects, you know, “Ozempic made my face saggy!” No, that’s called weight loss! I find that kind of social media misinformation very frustrating. And if people can't get the medication that they need for their disease because it's being used as a social drug? That is unacceptable to me.

But as someone more motivated by the basic science, biological side, I’ve simply continued to study how GLP-1 functions in the body. And over the past ten years or so, we’ve discovered that it’s part of the circadian system. This observation has shed more light on findings that shift workers, for example, are at much higher risk of obesity and type two diabetes. That’s been really unique, and really hard to study, because it involves 24 or even 48-hour experiments. My students have been amazing carrying all of that out. These new discoveries have been a really interesting way to end my career of studying GLP-1.

The Godmother of GLP-2

I’m proud of the work I did on GLP-1, but I think what I did on GLP-2 probably had a much bigger impact. My lab was the first, I think, to really show that GLP-2 promoted gut health as well as gut growth. Dan Drucker and I published our first paper on this observation in 1996, Dan then put the clinical wheels in motion, and by 2012 a drug was approved by the FDA for patients with a condition called short bowel syndrome. Unbelievably fast!

There was a time after that first paper when Daniel Drucker and I, working collaboratively, put out eight or ten papers in about two years, and everything we did was new because no one had known before that GLP-2 is an intestinal growth factor. So that was a golden period of time. It was really exciting. And this GLP-2 long acting receptor agonist drug is now used worldwide. The implication has been that people with short bowel syndrome, who once required exclusively IV feeding and fluids, can eat more normally, with twenty to thirty percent of them able to stop the IV’s altogether. An unbelievable game-changer. So I’m really proud of that.

I remember being at a conference once, and I went to look at the poster of a young scientist from Japan. He was very polite, very buttoned up, but when he saw me, he got excited, and he said, “Dr. Brubaker! You’re the godmother of GLP-2!” So that was a really nice moment.

Representation (and feminist leadership!) matters

As I said, my parents told me I could do whatever I wanted to do. So I never thought about being a woman in science, I didn’t dwell on that. But when I went to a biochemistry conference during my PhD, that was when it first really struck me: everyone there except for me, it seemed, was a man in a black suit and white shirt. The next year, I went to my first endocrinology conference. And there were women everywhere! That was the first experience when I said, “Hey, wait a minute, I can see myself here at this conference. I can’t see myself there.” I realized that biochemistry was not a place that I wanted to be.

But in that regard, the Department of Physiology has been fabulous. There were three women who were brought on board around the same time as me. And since then the representation of women in Physiology has only increased.

I mean, Harold Atwood was the Chair when I started, who had several women in his life who were well known artists – he had no choice but to be a feminist! I remember early on I went to Harold and said, “I don’t think you have enough junior faculty on your Senior Advisory Committee.” And he looked at me and said, “You’re right. You’re on the committee.” So he was always incredibly thoughtful. That was the system I entered into and 99% of it has been very, very positive.

Light your candle from mine

I've always had a tradition of having summer barbecues with my lab. And in some ways, those are the highlights of my career – everyone just eating and drinking and laughing together. Along with photographs of all of the students who have come through my lab, I’ve had this Thomas Jefferson quote on my wall for decades:

“Knowledge is like a candle. When you light your candle from mine, my light is not diminished. It is enhanced, and a larger room is enlightened as a consequence.”

And it’s all of the students who have enlightened my room. That is really what has kept me going.

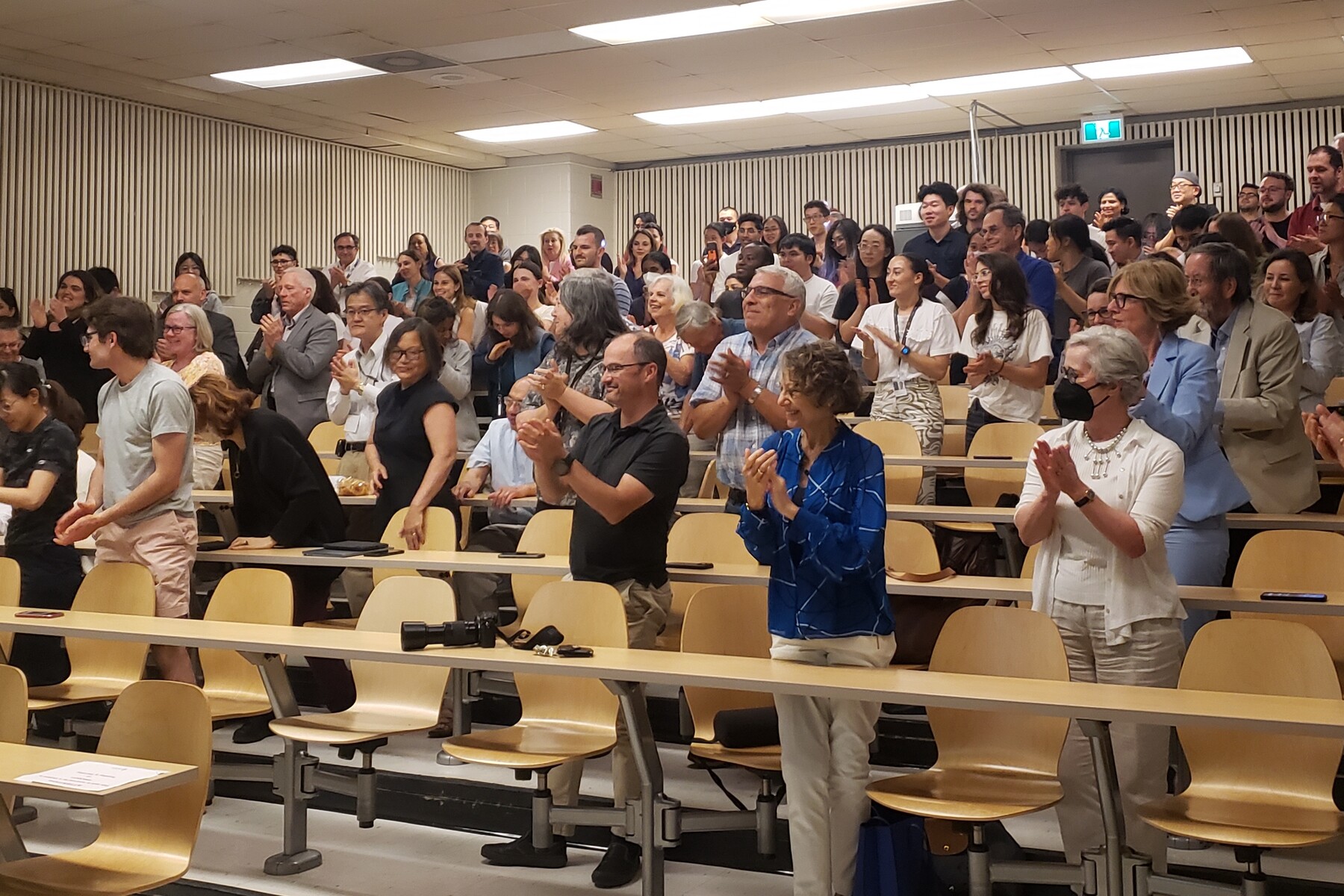

Dr. Brubaker ended her seminar with a slideshow of those photographs of students that adorned her office wall throughout the years, and was met with a standing ovation. An absolute pillar of the Department, Dr. Brubaker will be deeply missed. The legacy of her life-changing discoveries, uncompromised authenticity, and the countless candles she has lit will continue to shape Physiology in perpetuity. We wish Dr. Brubaker a wonderful retirement full of trekking, barbecues, laughter, Star Trek, and fun!